what is the four factors to which international business growth is attributed?

All our charts on Trade and Globalization

Trade has inverse the earth economy

Merchandise has grown remarkably over the terminal century

The integration of national economies into a global economical system has been one of the most of import developments of the last century. This process of integration, oftentimes chosen Globalization, has materialized in a remarkable growth in merchandise betwixt countries.

The chart hither shows the value of world exports over the period 1800-2014. These estimates are in constant prices (i.due east. have been adjusted to account for inflation) and are indexed at 1913 values.

This chart shows an extraordinary growth in international merchandise over the last couple of centuries: Exports today are more than than 40 times larger than in 1913.

Y'all tin click on the option marked 'Linear', on top of the vertical axis, to alter into a logarithmic scale. This will help yous encounter that, over the long run, growth has roughly followed an exponential path.

Trade has grown more than proportionately with GDP

The chart to a higher place shows how much more trade we have today relative to a century ago. But what nearly trade relative to total economical output?

Over the terminal couple of centuries the world economy has experienced sustained positive economic growth, and so looking at changes in merchandise relative to Gross domestic product offers another interesting perspective.

The side by side chart plots the value of trade in appurtenances relative to Gdp (i.e. the value of trade merchandise as a share of global economic output).

Upward to 1870, the sum of worldwide exports deemed for less than 10% of global output. Today, the value of exported appurtenances around the world is shut to 25%. This shows that over the last hundred years of economic growth, in that location has been more than than proportional growth in global merchandise.

(NB. In this nautical chart you can add countries by choosing the option on the bottom left; or y'all can compare countries around the world by clicking on 'Map' on the chart.)

Today trade is a fundamental function of economic activity everywhere

In today'southward global economic arrangement, countries exchange non only final products, but also intermediate inputs. This creates an intricate network of economic interactions that cover the whole world.

The interactive data visualization, created by the London-based information visualisation studio Kiln and the UCL Free energy Institute, gives us an insight into the complex nature of trade. It plots the position of cargo ships across the oceans.

Trade generates efficiency gains

The raw correlation between trade and growth

Over the terminal couple of centuries the globe economy has experienced sustained positive economic growth, and over the aforementioned menstruation, this process of economic growth has been accompanied by fifty-fifty faster growth in global trade.

In a similar way, if we await at land-level data from the concluding half century nosotros find that there is also a correlation between economical growth and trade: countries with higher rates of GDP growth also tend to have higher rates of growth in merchandise as a share of output. This basic correlation is shown in the nautical chart here, where we plot boilerplate almanac change in real Gross domestic product per capita, against growth in trade (average annual change in value of exports as a share of Gross domestic product).1

Is this statistical association between economic output and merchandise causal?

Among the potential growth-enhancing factors that may come from greater global economic integration are: Competition (firms that fail to adopt new technologies and cut costs are more probable to fail and to be replaced past more than dynamic firms); Economies of calibration (firms that can export to the world face larger demand, and under the correct conditions, they can operate at larger scales where the price per unit of measurement of production is lower); Learning and innovation (firms that merchandise proceeds more experience and exposure to develop and adopt technologies and industry standards from foreign competitors).2

Are these mechanisms supported by the data? Let'due south have a wait at the available empirical evidence.

Causality: Evidence from cross-state differences in trade, growth and productivity

When it comes to academic studies estimating the impact of trade on Gross domestic product growth, the most cited newspaper is Frankel and Romer (1999).3

In this study, Frankel and Romer used geography as a proxy for trade, in order to estimate the impact of trade on growth. This is a classic case of the so-called instrumental variable approach. The idea is that a land'southward geography is stock-still, and mainly affects national income through trade. So if nosotros observe that a state's distance from other countries is a powerful predictor of economic growth (after accounting for other characteristics), then the decision is fatigued that it must be because trade has an effect on economic growth. Following this logic, Frankel and Romer detect evidence of a strong impact of trade on economic growth.

Other papers have applied the same approach to richer cross-country data, and they have found similar results. A key instance is Alcalá and Ciccone (2004).iv

This torso of evidence suggests trade is indeed one of the factors driving national average incomes (Gross domestic product per capita) and macroeconomic productivity (Gross domestic product per worker) over the long run.v

Causality: Show from changes in labor productivity at the house level

If trade is causally linked to economical growth, nosotros would expect that trade liberalization episodes also lead to firms becoming more than productive in the medium, and even brusk run. There is bear witness suggesting this is often the example.

Pavcnik (2002) examined the effects of liberalized trade on plant productivity in the case of Chile, during the belatedly 1970s and early 1980s. She found a positive touch on on house productivity in the import-competing sector. And she also found show of aggregate productivity improvements from the reshuffling of resources and output from less to more efficient producers. 6

Bloom, Draca and Van Reenen (2016) examined the impact of rise Chinese import contest on European firms over the period 1996-2007, and obtained similar results. They found that innovation increased more in those firms most affected by Chinese imports. And they found show of efficiency gains through ii related channels: innovation increased and new existing technologies were adopted within firms; and amass productivity too increased because employment was reallocated towards more technologically avant-garde firms.vii

Wrapping up: Trade does generate efficiency gains

On the whole, the bachelor evidence suggests trade liberalization does improve economic efficiency. This show comes from unlike political and economical contexts, and includes both micro and macro measures of efficiency.

This upshot is important, because it shows that there are gains from trade. Only of course efficiency is non the but relevant consideration here. As nosotros discuss in a companion blog postal service, the efficiency gains from trade are non mostly equally shared by everyone. The evidence from the bear on of trade on firm productivity confirms this: "reshuffling workers from less to more efficient producers" means closing down some jobs in some places. Because distributional concerns are existent it is important to promote public policies – such as unemployment benefits and other safety-net programs – that assistance redistribute the gains from merchandise.

The conceptual link between trade and household welfare

When a country opens up to trade, the demand and supply of goods and services in the economic system shift. As a consequence, local markets respond, and prices modify. This has an impact on households, both equally consumers and as wage earners.

The implication is that trade has an impact on everyone. It'south not the case that the effects are restricted to workers from industries in the merchandise sector; or to consumers who buy imported goods. The effect of trade extends to anybody because markets are interlinked, so imports and exports have knock-on furnishings on all prices in the economy, including those in non-traded sectors.

Economists unremarkably distinguish between "general equilibrium consumption effects" (i.east. changes in consumption that arise from the fact that trade affects the prices of non-traded appurtenances relative to traded goods) and "general equilibrium income effects" (i.e. changes in wages that arise from the fact that trade has an bear upon on the demand for specific types of workers, who could be employed in both the traded and not-traded sectors).

Considering all these complex interrelations, information technology'due south non surprising that economic theories predict that not everyone volition do good from international trade in the same way. The distribution of the gains from trade depends on what different groups of people eat, and which types of jobs they have, or could have.

(NB. You can read more almost these economical concepts, and the related predictions from economic theory, in Chapter 18 of the textbook The Economy: Economics for a Changing World.)

The link between merchandise, jobs and wages

Evidence from Chinese imports and their affect on factory workers in the US

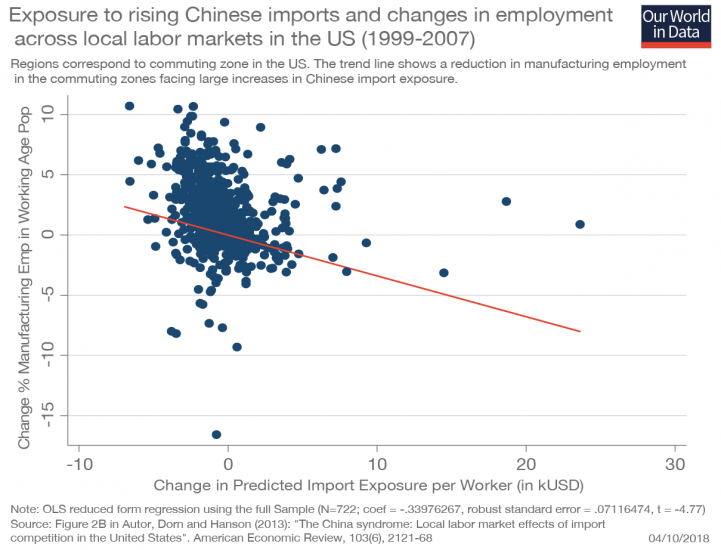

The most famous written report looking at this question is Autor, Dorn and Hanson (2013): "The Cathay syndrome: Local labor market effects important contest in the U.s.a.".viii

In this paper, Autor and coauthors looked at how local labor markets changed in the parts of the country most exposed to Chinese competition, and they found that ascension exposure increased unemployment, lowered labor force participation, and reduced wages. Additionally, they found that claims for unemployment and healthcare benefits too increased in more than merchandise-exposed labor markets.

The visualization here is one of the primal charts from their newspaper. It's a scatter plot of cross-regional exposure to rising imports, confronting changes in employment. Each dot is a small region (a 'commuting zone' to be precise). The vertical position of the dots represents the percent change in manufacturing employment for working age population; and the horizontal position represents the predicted exposure to rising imports (exposure varies across regions depending on the local weight of different industries).

The trend line in this chart shows a negative relationship: more than exposure goes together with less employment. In that location are large deviations from the trend (there are some low-exposure regions with big negative changes in employment); but the paper provides more sophisticated regressions and robustness checks, and finds that this relationship is statistically significant.

This result is of import considering information technology shows that the labor market adjustments were big. Many workers and communities were affected over a long flow of time.9

But it's likewise of import to go along in heed that Autor and colleagues are only giving the states a partial perspective on the total effect of merchandise on employment. In item, comparing changes in employment at the regional level misses the fact that firms operate in multiple regions and industries at the same time. Indeed, Ildikó Magyari recently found evidence suggesting the Chinese trade shock provided incentives for US firms to diversify and reorganize production.10

So companies that outsourced jobs to Cathay often concluded up closing some lines of business concern, only at the same fourth dimension expanded other lines elsewhere in the U.s.a.. This means that job losses in some regions subsidized new jobs in other parts of the land.

On the whole, Magyari finds that although Chinese imports may accept reduced employment within some establishments, these losses were more than commencement past gains in employment within the aforementioned firms in other places. This is no consolation to people who lost their job. Just information technology is necessary to add together this perspective to the simplistic story of "trade with China is bad for The states workers".

Exposure to rising Chinese imports and changes in employment across local labor markets in the Usa (1999-2007) – Autor, Dorn and Hanson (2013)

Testify from the expansion of trade in Bharat and the affect on poverty reductions

Another important newspaper in this field is Topalova (2010): "Factor immobility and regional impacts of merchandise liberalization: Evidence on poverty from Republic of india".xi

In this newspaper Topalova looks at the affect of trade liberalization on poverty beyond different regions in India, using the sudden and extensive change in India's trade policy in 1991. She finds that rural regions that were more than exposed to liberalization, experienced a slower decline in poverty, and had lower consumption growth.

In the analysis of the mechanisms underlying this effect, Topalova finds that liberalization had a stronger negative impact amid the least geographically mobile at the bottom of the income distribution, and in places where labor laws deterred workers from reallocating across sectors.

The evidence from Bharat shows that (i) discussions that simply await at "winners" in poor countries and "losers" in rich countries miss the point that the gains from trade are unequally distributed within both sets of countries; and (ii) context-specific factors, like worker mobility across sectors and geographic regions, are crucial to understand the impact of trade on incomes.

Evidence from other studies

- Donaldson (2018) uses archival data from colonial Bharat to estimate the touch on of India's vast railroad network. He finds railroads increased merchandise, and in doing then they increased existent incomes (and reduced income volatility).12

- Porto (2006) looks at the distributional effects of Mercosur on Argentine families, and finds this regional trade agreement led to benefits across the unabridged income distribution. He finds the effect was progressive: poor households gained more than than middle-income households, because prior to the reform, trade protection benefitted the rich disproportionately.13

- Trefler (2004) looks at the Canada-US Gratuitous Trade Understanding and finds there was a group who bore "adjustment costs" (displaced workers and struggling plants) and a group who enjoyed "long-run gains" (consumers and efficient plants). 14

The link betwixt trade and the price of living

The fact that trade negatively affects labor market opportunities for specific groups of people does not necessarily imply that trade has a negative amass effect on household welfare. This is because, while trade affects wages and employment, it also affects the prices of consumption goods. And then households are affected both as consumers and equally wage earners.

Near studies focus on the earnings channel, and try to guess the impact of trade on welfare past looking at how much wages can buy, using as reference the changing prices of a fixed basket of goods.

This approach is problematic because it fails to consider welfare gains from increased product variety, and obscures complicated distributional issues such as the fact that poor and rich individuals consume different baskets so they benefit differently from changes in relative prices.15

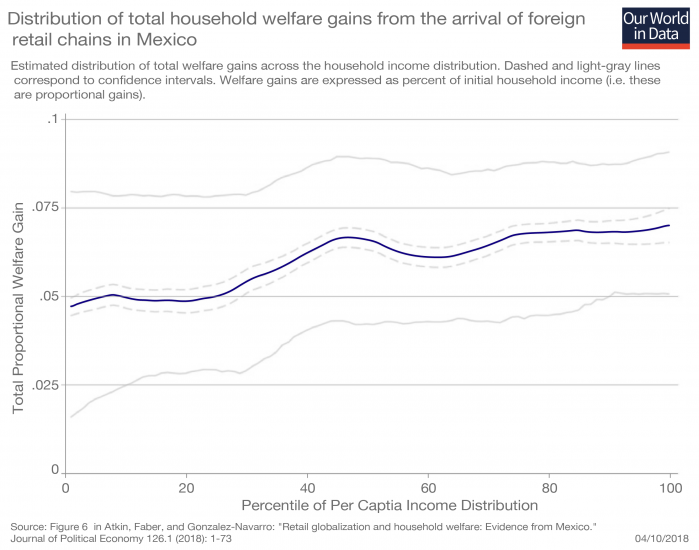

Ideally, studies looking at the impact of trade on household welfare should rely on fine-grained data on prices, consumption and earnings. This is the approach followed in Atkin, Faber, and Gonzalez-Navarro (2018): "Retail globalization and household welfare: Testify from United mexican states".16

Atkin and coauthors use a uniquely rich dataset from Mexico, and find that the arrival of global retail chains led to reductions in the incomes of traditional retail sector workers, but had little bear upon on average municipality-level incomes or employment; and led to lower costs of living for both rich and poor households.

The nautical chart here shows the estimated distribution of total welfare gains beyond the household income distribution (the lite-gray lines correspond to confidence intervals). These are proportional gains, and are expressed every bit percent of initial household income.

As we tin can come across, in that location is a net positive welfare effect across all income groups; but these improvements in welfare are regressive, in the sense that richer households gain proportionally more (nearly seven.v percent gain compared to five pct).17

Evidence from other countries confirms this is not an isolated case – the expenditure aqueduct really seems to be an important and understudied source of household welfare. Giuseppe Berlingieri, Holger Breinlich, Swati Dhingra, for instance, investigate the consumer benefits from trade agreements implemented by the European union betwixt 1993 and 2013; and they discover that these trade agreements increased the quality of bachelor products, which translated into a cumulative reduction in consumer prices equivalent to savings of €24 billion per year for Eu consumers.18

Distribution of total household welfare gains from the inflow of foreign retail chains in United mexican states – Atkin, Faber, and Gonzalez-Navarro (2018)

Wrapping up: Cyberspace welfare furnishings and implications

The available bear witness shows that, for some groups of people, merchandise has a negative effect on wages and employment opportunities; and at the same fourth dimension it has a large positive issue via lower consumer prices and increased availability of products.

2 points are worth emphasising.

For some households, the net effect is positive. But for some households that's not the case. In detail, workers who lose their job tin can be affected for extended periods of fourth dimension, so the positive upshot via lower prices is not enough to compensate them for the reduction in earnings.

On the whole, if we aggregate changes in welfare across households, the net issue is usually positive. But this is inappreciably a consolation for those who are worse off.

This highlights a circuitous reality: There are aggregate gains from trade, just there are besides real distributional concerns. Even if trade is not a major commuter of income inequalities, it's important to keep in mind that public policies, such as unemployment benefits and other safety-net programs, can and should help redistribute the gains from trade.

The "two waves of globalization"

The commencement "wave of globalization" started in the 19th century, the second one after WW2

The following visualization presents a compilation of available trade estimates, showing the evolution of globe exports and imports as a share of global economic output.

This metric (the ratio of total merchandise, exports plus imports, to global GDP) is known as the 'openness alphabetize'. The higher the index, the higher the influence of trade transactions on global economical activeness.nineteen

As we tin can see, until 1800 there was a long menstruum characterized by persistently low international trade – globally the index never exceeded ten% earlier 1800. This and then changed over the course of the 19th century, when technological advances triggered a menstruum of marked growth in world trade – the so-chosen 'first moving ridge of globalization'.

The showtime moving ridge of globalization came to an finish with the outset of the Start World War, when the decline of liberalism and the rise of nationalism led to a slump in international trade. In the chart we run across a large drop in the interwar period.

After the 2nd World War trade started growing once more. This new – and ongoing – wave of globalization has seen international trade abound faster than ever before. Today the sum of exports and imports across nations amounts to more 50% of the value of total global output.

(NB. Klasing and Milionis (2014), which is one of the sources in the chart, published an additional set up of estimates nether an alternative specification. Similarly, for the period 1960-2015, the World Bank'southward World Development Indicators published an alternative set of estimates, which are similar simply not identical to those included from the Penn Earth Tables (9.ane). You find all these alternative overlapping sources in this comparison chart.)

Before the showtime moving ridge of globalization, trade was driven mostly by colonialism

Over the early modern period, transoceanic flows of goods betwixt empires and colonies accounted for an of import function of international trade. The following visualizations provides a comparison of intercontinental trade, in per capita terms, for unlike countries.

As we can run into, intercontinental merchandise was very dynamic, with volumes varying considerably across time and from empire to empire.

Leonor Freire Costa, Nuno Palma, and Jaime Reis, who compiled and published the original information shown here, argue that merchandise, also in this period, had a substantial positive bear upon on the economic system.twenty

The get-go wave of globalization was marked by the ascension and collapse of intra-European merchandise

The post-obit visualization shows a detailed overview of Western European exports past destination. Figures represent to export-to-Gdp ratios (i.e. the sum of the value of exports from all Western European countries, divided past total Gross domestic product in this region). Using the option labeled 'relative', at the bottom of the chart, you tin can meet the proportional contribution of each region to full Western European exports.

This chart shows that growth in Western European trade throughout the 19th century was largely driven by merchandise within the region: In the period 1830-1900 intra-European exports went from 1% of GDP to 10% of GDP; and this meant that the relative weight of intra-European exports doubled over the menses (in the 'relative' view you can see the irresolute limerick of exports past destination, and you tin can bank check that the weight of intra-European trade went from about one tertiary to virtually ii thirds over the period). But this process of European integration then collapsed sharply in the interwar period.

After the Second World War trade inside Europe rebounded, and from the 1990s onwards exceeded the highest levels of the first wave of globalization. In addition Western Europe then started to increasingly trade with Asia, the Americas, and to a smaller extent Africa and Oceania.

The next graph, from Broadberry and O'Rourke (2010)21, shows another perspective on the integration of the global economy and plots the development of three indicators measuring integration across different markets – specifically goods, labor, and majuscule markets.

The indicators in this nautical chart are indexed, and so they show changes relative to the levels of integration observed in 1900. This gives united states of america another viewpoint to understand how speedily global integration collapsed with the two Globe Wars.

(NB. Integration in the goods markets is measured here through the 'merchandise openness index', which is divers by the sum of exports and imports as share of Gross domestic product. In this interactive chart you can explore trends in trade openness over this menses for a option of European countries.)

The 2nd wave of globalization was enabled by engineering

The world-wide expansion of trade subsequently the Second World War was largely possible considering of reductions in transaction costs stemming from technological advances, such as the development of commercial civil aviation, the comeback of productivity in the merchant marines, and the democratization of the telephone as the main way of communication. The visualization shows how, at the global level, costs beyond these three variables have been going down since 1930.

The reductions in transaction costs had an impact, non only on the volumes of trade, only as well on the types of exchanges that were possible and profitable.

The kickoff wave of globalization was characterized by inter-industry merchandise. This means that countries exported goods that were very different to what they imported – England exchanged machines for Australian wool and Indian tea. As transaction costs went down, this changed. In the second wave of globalization nosotros are seeing a ascension in intra-industry merchandise (i.eastward. the commutation of broadly like goods and services is condign more and more than common). France, for example, now both imports and exports machines to and from Germany.

The following visualization, from the UN World Development Written report (2009), plots the fraction of total world trade that is deemed for by intra-industry merchandise, past type of goods. Every bit we can encounter, intra-industry trade has been going up for chief, intermediate and final goods.

This blueprint of merchandise is important because the scope for specialization increases if countries are able to commutation intermediate goods (east.g. automobile parts) for related terminal goods (e.g. cars).

Two centuries of trade, country past land

In a higher place nosotros took a look at the wide global trends over the last two centuries. Let's now zoom in on country-level trends over this long and dynamic period.

This chart plots estimates of the value of trade in appurtenances, relative to total economic activity (i.e. export-to-GDP ratios).

These historical estimates plain come up with a large margin of error (in the measurement department below nosotros talk over the data limitations); all the same they offer an interesting perspective.

Yous can add more serial past clicking on the choice ' Add together country '. Each land tells a unlike story. If you add the Netherlands, for example, you volition see how important the Dutch Golden Age was.

(NB. Here is the same chart only showing imports, rather than exports.)

Irresolute trade partners

In the adjacent chart we plot, country by country, the regional breakdown of exports. India is shown by default, but you lot can switch land using the pick 'Change entity'.

Using the option 'relative', at the bottom of the chart, you lot tin can see the proportional contribution of purchases from each region. For example: We see that 48% of the full value of Indian exports in 2014 went to Asian countries.

This gives usa an interesting perspective on the changing nature of merchandise partnerships. In India, we see the rise importance of trade with Africa – this is a pattern that we hash out in more detail below.

How much practice countries merchandise?

Trade openness around the earth

The and so-called trade openness alphabetize is an economical metric calculated as the ratio of state's total trade (the sum of exports plus imports) to the country's gross domestic product.

This metric gives the states an idea of integration, because information technology captures all incoming and outgoing transactions. The higher the index the larger the influence of trade on domestic economical activities.

The visualization presents a earth map showing the trade openness index country by country. You can explore country-specific time series past clicking on a country, or past using the 'Chart' tab.

For whatsoever given year, nosotros see that in that location is a lot of variation across countries. The weight of trade in the Us economy, for example, is much lower than in other rich countries.

If yous press the play button in the map, you can see changes over time. This reveals that, despite the great variation between countries, at that place is a mutual trend: Over the concluding couple of decades trade openness has gone upward in nearly countries.

Exports and imports in real dollars

Expressing trade values as a share of GDP tells us the importance of merchandise in relation to the size of economical activity. Let's now take a look at trade in monetary terms – this tells us the importance of merchandise in absolute, rather than relative terms.

The chart shows the value of exports (appurtenances plus services) in dollars, country by country. All estimates are expressed in constant 2010 dollars (i.e. all values have been adjusted to correct for inflation).

The primary takeaway here are the country-specific trends, which are positive and more pronounced than in the charts showing shares of Gdp. This is not surprising: most countries today produce more a couple of decades ago; and at the same fourth dimension they trade more of what they produce.

You can plot trends by region using the pick ' Add country '.

(NB. Here is the aforementioned nautical chart, but showing imports rather than exports.)

What practise countries trade?

Merchandise in goods vs Trade in services

Trade transactions include goods (tangible products that are physically shipped across borders by road, rail, h2o, or air) and services (intangible bolt, such as tourism, financial services, and legal advice).

Many traded services make merchandise merchandise easier or cheaper—for instance, aircraft services, or insurance and fiscal services.

Merchandise in appurtenances has been happening for millenia; while trade in services is a relatively recent phenomenon.

In some countries services are today an important driver of merchandise: In the UK services account for about 45% of all exports; and in the Bahamas almost all exports are services (virtually 87% in 2016).

In other countries the opposite is true: In Nigeria and Venezuela services accounted for around 2% and iii% of exports, respectively, in 2014.

Globally, trade in goods accounts for the majority of trade transactions. But every bit this chart shows, the share of services in total global exports has increased, from 17% in 1979 to 24% in 2017.

(NB. This interactive chart shows merchandise in services as share of Gross domestic product across countries and regions.)

Domestic vs Foreign value added in exports

Firms around the globe import goods and services, in order to use them as inputs to produce goods and services that are later exported. The imported goods and services incorporated in a country'south exports are a key indicator of economical integration – they tell us something almost 'global value chains', where the different stages of the production process are located across different countries.

The chart, from UNCTAD's World Investment Report 2018 – Investment and New Industrial Policies, shows trends of gross exports, broken downwards into domestic and strange value added. That is, the share of the value of exports that comes from foreign inputs.

Today, nearly 30% of the value of global exports comes from foreign inputs. In 1990, the share was about 25%.

Foreign value added in trade peaked in 2010–2012 afterward two decades of continuous increase. This is consistent with the fact that, subsequently the global fiscal crisis, there has been a slowdown in the rate of growth of trade in goods and services, relative to global Gdp. This is a sign that global integration stalled after the financial crisis.

(NB. The integration of global value chains is a mutual source of measurement fault in trade data, because it makes it difficult to correctly attribute the origin and destination of goods and services. We discuss this in more detail beneath.)

How are trade partnerships changing?

Bilateral trade is becoming increasingly mutual

If we consider all pairs of countries that engage in trade around the world, nosotros find that in the majority of cases, there is a bilateral relationship today: Near countries that consign goods to a country, also import goods from the aforementioned state.

The interactive visualization shows this.23

In this chart, all possible state pairs are partitioned into three categories: the peak portion represents the fraction of land pairs that practice not trade with ane-some other; the middle portion represents those that trade in both directions (they export to i-another); and the bottom portion represents those that trade in one direction only (one country imports from, but does not export to, the other country).

As nosotros can see, bilateral merchandise is becoming increasingly mutual (the middle portion has grown substantially). But it remains truthful that many countries notwithstanding do not trade with each other at all (in 2014 about 25% of all country-pairs recorded no merchandise).

South-South trade is becoming increasingly important

The visualization here shows the share of globe merchandise trade that corresponds to exchanges betwixt today's rich countries and the rest of the world.

The 'rich countries' in this nautical chart are: Commonwealth of australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Cyprus, Kingdom of denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Republic of ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Kingdom of norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom and the United states of america. 'Non-rich countries' are all the other countries in the globe.

As we tin can see, upwardly until the Second World War the bulk of trade transactions involved exchanges between this modest group of rich countries. Only this has been irresolute quickly over the last couple of decades, and today trade between not-rich countries is simply as important as trade between rich countries.

In the past 2 decades China has been a cardinal driver of this dynamic: the UN Homo Development Study (2013) estimates that between 1992 and 2011, China's trade with Sub-Saharan Africa rose from $one billion to more than than $140 billion.

(NB. Hither is a stacked area chart showing the total composition of exports past partnership. Information technology'due south the same data, but plotted with stacked series.)

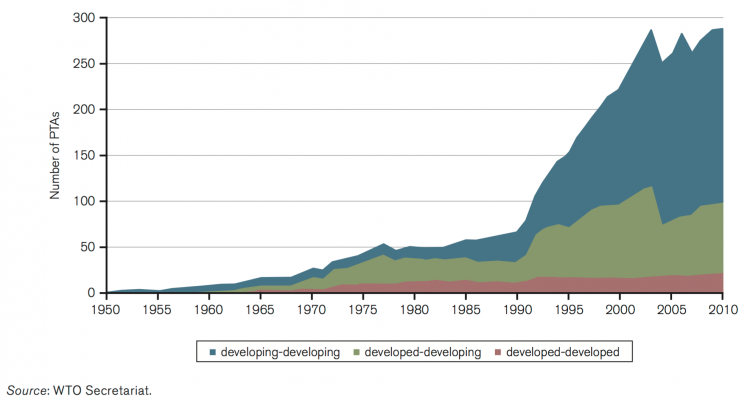

The majority of preferential trade agreements are betwixt emerging economies

The last few decades take non only seen an increase in the volume of international trade, only also an increase in the number of preferential merchandise agreements through which exchanges take place. A preferential trade agreement is a trade pact that reduces tariffs between the participating countries for sure products.

The visualization here shows the development of the cumulative number of preferential trade agreements that are in forcefulness beyond the globe, according to the World Trade Organization (WTO). These numbers include notified and non-notified preferential agreements (the source reports that just about two-thirds of the agreements currently in strength have been notified to the WTO), and are disaggregated by state groups.

This figure shows the increasingly of import role of trade between developing countries (S-Southward trade), vis-a-vis trade between developed and developing countries (Due north-S merchandise). In the tardily 1970s, North-Southward agreements accounted for more than half of all agreements – in 2010, they accounted for most one quarter. Today, the majority of preferential trade agreements are betwixt developing economies.

Number of preferential trade agreements in strength by country grouping, 1950-2010 – Figure B1 in WTO Merchandise Report (2011)

Trading patterns have been changing chop-chop in middle income countries

The increase in merchandise amongst emerging economies over the last half century has been accompanied by an important change in the composition of exported appurtenances in these countries.

The adjacent visualization plots the share of food exports in each country'southward full exported merchandise. These figures, produced by the Globe Depository financial institution, correspond to the Standard International Trade Classification, in which 'food' includes, amidst other goods, live animals, beverages, tobacco, coffee, oils, and fats.

Two points stand up out. First, at that place has been a substantial decrease in the relative importance of food exports since 1960s in nearly countries (although globally in the last decade it has gone upwards slightly). And second, this decrease has been largest in middle income countries, particularly in Latin America. Colombia is a notable instance in betoken: nutrient went from 77% of merchandise exports in 1962, to 15.9% in 2015.

Regarding levels, as one would wait, in high income countries food still accounts for a much smaller share of merchandise exports than in well-nigh low- and centre-income-countries.

Explaining merchandise patterns: Theory and Show

- Comparative advantage

- Trade diminishes with distance

- Institutions

- Increasing returns to scale

Comparative advantage

Theory: What is 'comparative advantage' and why does it matter to understand trade?

In economic theory, the 'economical cost' – or the 'opportunity toll' – of producing a proficient is the value of everything you need to surrender in order to produce that good.

Economic costs include physical inputs (the value of the stuff you apply to produce the good), plus forgone opportunities (when you allocate deficient resources to a task, you give up alternative uses of those resources).

A country or a person is said to take a 'comparative advantage' if they take the power to produce something at a lower opportunity cost than their trade partners.

The forgone opportunities of product are key to empathise this concept. Information technology is precisely this that distinguishes absolute advantage from comparative reward.

To see the departure betwixt comparative and absolute advantage, consider a commercial aviation pilot and a baker. Suppose the pilot is an excellent chef, and she can bake but as well, or even improve than the baker. In this case, the pilot has an accented advantage in both tasks. Yet the baker probably has a comparative advantage in baking, because the opportunity toll of baking is much higher for the pilot.

The freely available economics textbook The Economy: Economic science for a Changing World explains this as follows: "A person or country has comparative reward in the production of a particular expert, if the cost of producing an additional unit of that good relative to the cost of producing another good is lower than some other person or country's cost to produce the aforementioned 2 goods."

At the individual level, comparative advantage explains why y'all might want to delegate tasks to someone else, fifty-fifty if you can do those tasks better and faster than them. This may audio counterintuitive, but it is not: If you are good at many things, it means that investing fourth dimension in one job has a high opportunity cost, because you are not doing the other astonishing things you could be doing with your time and resources. So, at to the lowest degree from an efficiency indicate of view, you should specialize on what you are all-time at, and delegate the rest.

The aforementioned logic applies to countries. Broadly speaking, the principle of comparative advantage postulates that all nations can gain from merchandise if each specializes in producing what they are relatively more efficient at producing, and import the rest: "do what you practise all-time, import the rest".24

In countries with relative abundance of certain factors of production, the theory of comparative advantage predicts that they will consign goods that rely heavily in those factors: a country typically has a comparative advantage in those goods that utilise more intensively its abundant resources. Colombia exports bananas to Europe considering information technology has insufficiently arable tropical atmospheric condition. Under autarky, Republic of colombia would find it cheap to produce bananas relative to eastward.thou. apples.

Bear witness: Is there empirical support for comparative-advantage theories of merchandise?

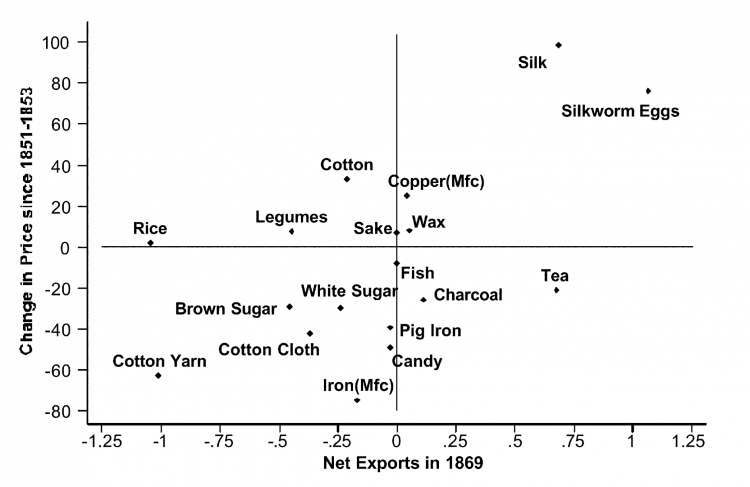

The empirical evidence suggests that the principle of comparative reward does aid explain trade patterns. Bernhofen and Brown (2004)25, for case, provide testify using the experience of Nihon. Specifically, they exploit Nihon's dramatic nineteenth-century motility from a land of almost consummate isolation to wide merchandise openness.

The graph here shows the price changes of the key tradable goods later the opening up to trade. It presents a besprinkle diagram of the net exports in 1869 graphed in relation to the change in prices from 1851–53 to 1869. As we can see, this is consistent with the theory: later on opening to trade, the relative prices of major exports such as silk increased (Japan exported what was cheap for them to produce and which was valuable abroad), while the relative toll of imports such as sugar declined (they imported what was relatively more difficult for them to produce, just was cheap abroad).

Internet exports and price changes for 1869, Japan – Effigy 4 in Bernhofen and Brown (2014)26

Trade diminishes with distance

The resistance that geography imposes on trade has long been studied in the empirical economic science literature – and the main conclusion is that trade intensity is strongly linked to geographic altitude.

The visualization, from Eaton and Kortum (2002)27, graphs 'normalized import shares' against distance. Each dot represents a country-pair from a ready of 19 OECD countries, and both the vertical and horizontal axis are expressed on logarithmic scales.

The 'normalized import shares' in the vertical axis provide a measure of how much each country imports from different partners (encounter the newspaper for details on how this is calculated and normalised), while distance in the horizontal axis corresponds to the distance between cardinal cities in each country (see the paper and references therein for details on the list of cities). As we tin see, there is a potent negative relationship. Trade diminishes with distance. Through econometric modeling, the paper shows that this relationship is non simply a correlation driven by other factors: their findings propose that altitude imposes a significant bulwark to trade.

The fact that trade diminishes with distance is also corroborated by information of trade intensity within countries. The visualization here shows, through a series of maps, the geographic distribution of French firms that export to France'south neighboring countries. The colors reflect the pct of firms which export to each specific state. As nosotros can run into, the share of firms exporting to each of the corresponding neighbors is largest close to the border. The authors also testify in the newspaper that this design holds for the value of private-firm exports – merchandise value decreases with distance to the border.

Institutions

Conducting international merchandise requires both financial and non-fiscal institutions to support transactions. Some of these institutions are fairly obvious (e.k. law enforcement); just some are less obvious. For instance, the bear witness shows that producers in exporting countries oftentimes need credit in order to appoint in trade.

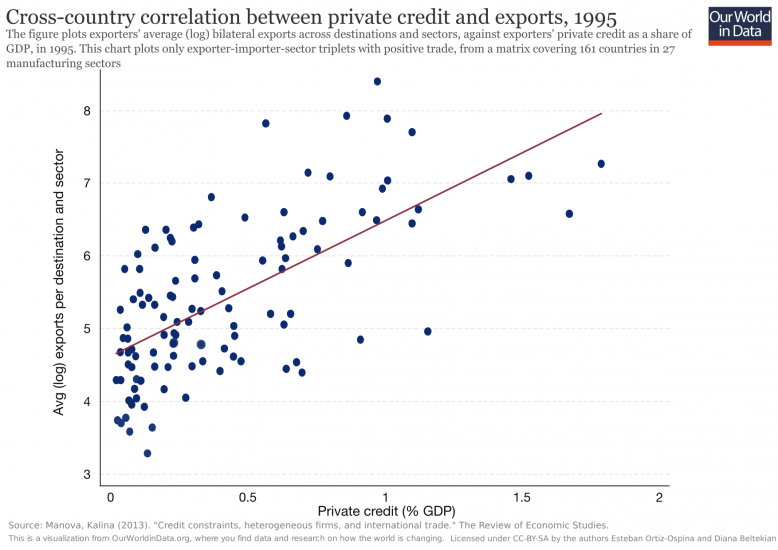

The scatter plot, from Manova (2013)thirty, shows the correlation betwixt levels in private credit (specifically exporters' private credit equally a share of GDP) and exports (boilerplate log bilateral exports across destinations and sectors). As tin can exist seen, financially adult economies – those with more dynamic private credit markets – typically outperform exporters with less evolved financial institutions.

Other studies take shown that country-specific institutions, similar the knowledge of foreign languages, for instance, are also important to promote foreign relative to domestic trade (see Melitz 200831).

Cross-state correlation between private credit and exports – Figure two in Manova (2013)32

Increasing returns to scale

The concept of comparative reward predicts that if all countries had identical endowments and institutions, then there would be little incentives for specialization, because the opportunity cost of producing any adept would be the same in every country.

Then you lot may wonder: why is it then the case that in the final few years we have seen such rapid growth in intra-industry merchandise between rich countries?

The increase in intra-manufacture between rich countries seems paradoxical under the light of comparative advantage, because in contempo decades we have seen convergence in cardinal factors, such as human capital, beyond these countries.

The solution to the paradox is actually non very complicated: Comparative advantage is one, but not the but forcefulness driving incentives to specialization and trade.

Several economists, nigh notably Paul Krugman, have developed theories of trade in which trade is not due to differences between countries, but instead due to "increasing returns to scale" – an economic term used to announce a applied science in which producing extra units of a proficient becomes cheaper if you operate at a larger scale.

The idea is that specialization allows countries to reap greater economies of calibration (i.eastward. to reduce production costs by focusing on producing big quantities of specific products), then trade can exist a good thought even if the countries practice not differ in endowments, including civilization and institutions.

These models of trade, oft referred to as 'New Merchandise Theory', are helpful to explain why in the last few years we have seen such rapid growth in two-mode exchanges of goods inside industries between developed nations.

In a much cited paper, Evenett and Keller (2002)33 show that both factor endowments and increasing returns assist explicate production and trade patterns around the world.

You lot can learn more about New Merchandise Theory, and the empirical back up behind it, in Krugman's Nobel lecture.

There are dozens of official sources of data on international trade, and if y'all compare these different sources, you lot will find that they practise not agree with one another. Even if y'all focus on what seems to be the aforementioned indicator for the same year in the same country, discrepancies are large.

For instance, for China in 2010, the estimated total value of goods exports was $1.48 trillion according to World Banking company Information, but it was $one.58 trillion according to WTO Data. That'due south a divergence of about 7%, or a hundred billion Us dollars.

Such differences betwixt sources can also be found for rich countries where statistical agencies tend to follow international reporting guidelines more closely. In Italian republic, for instance, Eurostat figures of the value of exported goods in 2015 are 10% higher than the trade trade figures published by the OECD.

And at that place are also large bilateral discrepancies within sources. Co-ordinate to IMF data, for example, the value of appurtenances that Canada reports exporting to the US is almost $20 billion more that the value of goods that the US reports importing from Canada.

Here nosotros explain how international trade data is nerveless and candy, and why there are such large discrepancies.

What information is available?

How big are discrepancies betwixt sources?

In the visualization hither we provide a comparison of the data published past several of the sources listed above, country by country, since 1955 upwards until today.

For each country, we exclude trade in services, and we focus only on estimates of the total value of exported appurtenances, expressed every bit shares of Gross domestic product.37

Every bit we tin can clearly see in this chart, different data sources tell often very different stories. And this is truthful, to varying degrees, across all countries and years. You can use the pick labeled 'change state', at the bottom of the chart, to focus on whatsoever country.

Constructing this chart was enervating. It required downloading trade data from many different sources, collecting the relevant series, and and so standardising them so that the units of mensurate and the geographical territories were consistent.

All serial, except the 2 long-run serial from CEPII and NBER-UN, were produced from data published past the sources in current US dollars, and and then converted to Gdp shares using a unique source (Earth Bank).38

So, if all series are in the same units (share of national GDP), and they all measure the same thing (value of goods exported from one country to the residue of the globe), what explains the differences?

Let'due south dig deeper to understand what'south going on.

Why doesn't the data add up?

Differences in guidelines used by countries to record and study trade data

Broadly speaking, there are two chief approaches used to estimate international merchandise merchandise:

- The commencement approach relies on estimating merchandise from customs records, often complementing or correcting figures with data from enterprise surveys and administrative records associated with taxation. The main manual providing guidelines for this approach is the International Merchandise Trade Statistics Manual (IMTS).

- The 2d approach relies on estimating trade from macroeconomic data, typically National Accounts. The main manual providing guidelines for this approach is the Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual (BPM6), which was drafted in parallel with the 2008 System of National Accounts of the Un (SNA 2008). The thought behind this arroyo is recording changes in economic ownership.39

Under these ii approaches, information technology is mutual to distinguish between 'traded trade' and 'traded goods'. The stardom is ofttimes fabricated because goods simply being transported through a state (i.e. goods in transit) are not considered to change the stock of material resources of a land, and are hence ofttimes excluded from the more than narrow concept of 'merchandise trade'.

Also, adding to the complexity, countries oftentimes rely on measurement protocols that are developed alongside these approaches and concepts that are non perfectly compatible to begin with. In Europe, for case, countries use the 'Compilers guide on European statistics on international trade in goods'.

Measurement error and other inconsistencies

Even when two sources rely on the same broad accounting approach, discrepancies arise considering countries fail to adhere perfectly to the protocols.

In theory, for instance, the exports of land A to state B should mirror the imports of country B from country A. But in practice this is rarely the case because of differences in valuation. Co-ordinate to the BPM6, imports and exports should be recorded in the balance of payments accounts on a 'gratuitous on board (Pull a fast one on) ground', which means using prices that include all charges up to placing the goods on board a ship at the port of departure. Even so many countries stick to Play tricks values just for exports, and utilise CIF values for imports (CIF stands for 'Cost, Insurance and Freight', and includes the costs of transportation).40

The chart here gives you lot an idea of how big import-consign asymmetries are. Shown are the differences between the value of appurtenances that each country reports exporting to the U.s., and the value of goods that the Usa reports importing from the same countries. For example, for People's republic of china, the figure in the chart corresponds to the "Value of merchandise imports in the The states from Cathay" minus "Value of merchandise exports from China to the United states of america".

The differences in the chart hither, which are both positive and negative, suggest that there is more than going on than differences in FOB vs CIF values. If all asymmetries were coming from CIF-FOB differences, then we should only see positive values in the chart (recollect that, unlike FOB values, CIF values include the price of transportation, and so CIF values are larger).

What else is going on here?

Another common source of measurement error relates to the inconsistent attribution of trade partners. An instance is failure to follow the guidelines on how to treat appurtenances passing through intermediary countries for processing or merchanting purposes. As global product chains become more complex, countries find information technology increasingly hard to unambiguously establish the origin and final destination of merchandise, even when rules are established in the manuals. 41

And at that place are still more potential sources of discrepancies. For example differences in customs and tax regimes, and differences between "general" and "special" trade systems (i.due east. differences betwixt statistical territories and actual state borders, which do not oft coincide because of things similar 'custom free zones').42

Even when two sources have identical trade estimates, inconsistencies in published data can arise from differences in substitution rates. If a dataset reports cross-country trade information in United states of america dollars, estimates will vary depending on the exchange rates used. Different exchange rates volition lead to conflicting estimates, even if figures in local currency units are consistent.

Wrapping upwardly

Asymmetries in international trade statistics are large and they ascend for a diversity of reasons. These include conceptual inconsistencies across measurement standards, as well as inconsistencies in the way countries apply agreed protocols. Here's a checklist of issues to keep in heed when comparing sources.

- Differences in underlying records: is trade measured from National Accounts data rather than direct from custom or tax records?

- Differences in import and export valuations: are transactions valued at Play a joke on or CIF prices?

- Inconsistent attribution of trade partners: how is the origin and concluding destination of trade established?

- Deviation between 'goods' and 'trade': how are re-importing, re-exporting, and intermediary merchanting transactions recorded?

- Exchange rates: how are values converted from local currency units to the currency that allows international comparisons (most often the United states-$)?

- Differences between 'full general' and 'special' trade system: how is trade recorded for custom-costless zones?

- Other bug: Time of recording, confidentiality policies, product classification, deliberate misinvoicing for illicit purposes.

These factors have long been recognized past many organizations producing trade data. Indeed, international organizations often comprise corrections, in an attempt to meliorate information quality along these lines.

The OECD's Balanced International Merchandise Merchandise Statistics, for example, uses its ain approach to right and reconcile international merchandise trade statistics.43

The corrections practical in the OECD's 'balanced' series make this the all-time source for cross-country comparisons. However, this dataset has low coverage across countries, and it only goes back to 2011. This is an important obstacle, since the complex adjustments introduced by the OECD imply we can't easily ameliorate coverage by appending data from other sources. At Our Earth in Information we have chosen to rely on CEPII equally the principal source for exploring long-run changes in international trade; just we too rely on Earth Banking concern and OECD data for up-to-date cross-country comparisons.

At that place are two central lessons from all of this. The first lesson is that, for well-nigh users of trade data out in that location, there is no obvious way of choosing between sources. And the second lesson is that, considering of statistical glitches, researchers and policymakers should always take analysis of merchandise data with a compression of common salt. For example, in a contempo high-profile report, researchers attributed mismatches in bilateral trade data to illicit financial flows through merchandise misinvoicing (or merchandise-based money laundering). Every bit we bear witness here, this interpretation of the data is not appropriate, since mismatches in the data can, and oftentimes do arise from measurement inconsistencies rather than malfeasance.44

Hopefully the discussion and checklist above can help researchers better interpret and choose between conflicting information sources.

Data Sources

International Historical Statistics (by Brian Mitchell)

- Data: Aggregate trade (current value), bilateral merchandise with main trading partners (current value), and major commodity exports by master exporting countries. No data on trade as share of Gdp is readily bachelor.

- Geographical coverage: Countries around the world

- Time span: Long time series with annual observations – from 19th century up to today (2010)

- Available at: The books are published in three volumes covering more than 5000 pages.45

At some universities y'all tin access the online version of the books where information tables can be downloaded as ePDFs and Excel files. The online access is here.

Penn Globe Tables

- Data: Real and PPP-adjusted Gdp in United states millions of dollars, national accounts (household consumption, investment, government consumption, exports and imports), exchange rates and population figures.

- Geographical coverage: Countries around the world

- Fourth dimension span: from 1950-2017 (version nine.1)

- Available at: Online hither

- Feenstra, Robert C., Robert Inklaar and Marcel P. Timmer (2015), "The Next Generation of the Penn World Table" forthcoming American Economical Review, available for download at www.ggdc.cyberspace/pwt

Correlates of War Bilateral Merchandise

- Information: Full national trade and bilateral trade flows between states. Total imports and exports of each country in current US millions of dollars and bilateral flows in electric current United states millions of dollars

- Geographical coverage: Single countries effectually the world

- Fourth dimension span: from 1870-2009

- Available at: Online at www.correlatesofwar.org

- This data set is hosted past Katherine Barbieri, Academy of Southward Carolina, and Omar Keshk, Ohio State Academy. Authors note in their 'Cow Trade Data Ready Codebook': "Nosotros advise against using the dyadic data file to produce any national or global totals, based on aggregations of the partner trade."

World Banking concern – Earth Development Indicators

- Information: Trade (% of GDP) and many more specific series: trade in merchandise, trade in services, trade in loftier-technology, merchandise in ICT goods, trade in ICT services – e'er exports and imports separately. Also export and import value alphabetize and volume index.

- Geographical coverage: Countries and earth regions

- Fourth dimension span: Annual since 1960

- Available at: Online at http://data.worldbank.org

United nations Comtrade

- Data: Bilateral trade flows past commodity

- Geographical coverage: Countries around the world

- Time span: 1962-2013

- Available at: Online here

- Bilateral trade flows can be sorted by goods or services, monthly or annually, with choice of nomenclature (including HS codes, SITC, and BEC). Data is likely to be very fourth dimension consuming to collate as there is no bulk data download unless a user has a premium site license.

UNCTADstat

- Data: Many dissimilar measures, including trade past volumes and value

- Geographical coverage: Countries around the world

- Time bridge: For some series, data is bachelor since 1948 – mostly almanac, sometimes quarterly.

- Available at: Online here

- UNCTADstat reports export and import information between 1995 and 2016 simply primarily to unlike regional groupings than any i land, and then it's probably not best suited to comparing land-to-country bilateral flows.

Eurostat – COMEXT

- Data: Merchandise flows (also by article)

- Geographical coverage: Europe (Eu and EFTA)

- Fourth dimension span: Mostly since 1988

- Bachelor at: Online here

- Also, the Eurostat website 'Statistics Explained' publishes upwardly-to-date statistical information on international trade in goods and services.

World Trade Organization – WTO

- Data: Many series on tariffs and merchandise flows

- Geographical coverage: Countries effectually the world

- Fourth dimension span: Since 1948 for some series

- Available at: Online here

- The WTO offers a bulk download of trade datasets which can be plant hither. Amongst these are annual WTO merchandise trade values and WTO-UNCTAD-ITC annual trade in services datasets. The former is available from 1948 – 2017, workable, with very little boosted formatting needed. However, observations are land groups, such as the EU28, the BRICS etc. rather than country-by-country values. Otherwise, the WTO's Statistics Database (SDB) has all-encompassing time series on international trade, by country with their trading partners. Once more, trading partners are primarily restricted to country groupings rather than individual nations.

Fouquin and Hugot (CEPII 2016) – TRADHIST dataset

- Data: Many different data sets related to international trade, including trade flows by commodity geographical variables, and variables to estimate gravity models

- Geographical coverage: Countries effectually the world

- Available at: Online here

- TRADHIST Bilateral Merchandise Historical Series: New Dataset 1827-2014 provides extensive dyadic merchandise data, with 97 percent of the observations from 1948 to today drawing on the IMF'due south Direction of Trade Statistics (DOTS) dataset.

NBER-United nations Trade Information, 1962-2000

- Information: Export and import values and volumes by article

- Geographical coverage: Single countries

- Time span: 1962-2000

- Available at: Online here

- This data is likewise available from the Middle for International Data. Bilateral merchandise data value estimates are very close to that of the World Bank's imports of appurtenances and services time serial.

Federico-Tena World Trade Historical Database

- Information: This website contains annual series of trade by polity from 1800 to 1938 which sum as series for continent and globe.

- Geographical coverage: Countries around the world

- Time span: 1800-1938

- Available at: Federico, Thousand., Tena Junguito, A. (2016). World trade, 1800-1938: a new data-prepare. EHES Working Papers in Economic History, n. 93. Online hither

Other historical merchandise data sets

- Data on United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland bilateral trade for the time 1870-1913 was collected by David South. Jacks. Information technology is downloadable in excel format here.

- For the time 1870-1913 21,000 bilateral trade observations tin can be found in Mitchener and Weidenmier (2008) – Merchandise and empire, bachelor in the Economic Journal here.

- Data on Uk, Germany, France, and United states between mid-19th to 20th Century can be institute hither.

- Data on Developing Country Export – in 1840, 1860, 1880 and 1900 – by John Hanson is available here.

- Data ontrade between England and Africa during the period 1699-1808 is available on the Dutch Information Archiving and Networked Services. It was compiled by Marion Johnson.

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/trade-and-globalization

0 Response to "what is the four factors to which international business growth is attributed?"

Post a Comment